Orchestral Excerpt Thoughts - The Miraculous Mandarin

This article will appear in the October 2016 International Trombone Journal (www.trombone.net), and I thought I would also post it here, as I would like to welcome any thoughts regarding the topic. Again, I'd like to thank Dennis Bubert for inviting me to write this article. If you are interested in this article please consider becoming a member of the International Trombone Association, as there are "must-see" articles in every issue

I don't consider myself a writer, and you can probably tell by a lot of my chicken scratch - but I learned a lot in this process! I hope you enjoy reading it, and by all means, do leave a comment, as an article like this isn't really meant to be the final word, but rather a jumping off point to further discussion. .- SL

-------------

I’ll never forget the first time I was introduced to Bartók’s Miraculous Mandarin. I was a sophomore at Indiana University in 1993, and was lucky enough to be in attendance at a masterclass with the Chicago Symphony low brass. It was an amazing showcase of excerpt after excerpt—they must have played a dozen or so orchestral excerpts, and I was totally immersed with everything they played— Brahms, Berlioz, Wagner.

Then it happened—they played something I had never heard before. They didn’t introduce it, so I had no idea what it was or what to expect. They played something so intense and so visceral that

it made me want to jump out of my skin. Independent lines. Glissandi everywhere. I was perplexed to see Jay Friedman put his horn down for a few bars while the organized chaos ensued. Was that actually in the part? I even wondered if they were all playing the same excerpt! But then—it suddenly made sense, as they ended the excerpt with such authority that, of course, there were no mistakes by the CSO low brass. A delayed shock rippled through the audience, as the effect was unlike the other excerpts. And they STILL didn’t tell us what this was. A violinist friend, who was also studying to be a conductor, instantly knew, and informed me that it was the end of the Suite to Miraculous Mandarin.

I think it’s safe to say that because of the complexity of the score, and possibly because of the subject matter, it’s on rare occasion that a university or conservatory will perform this music. However, because it is frequently performed at the professional level, certain excerpts do show up in auditions. From a performance perspective, no piece of music I have ever performed accelerates my heart rate quite like the Miraculous Mandarin.

For the remainder of this article, my goal is to describe how one might approach some of the most commonly requested excerpts to the The Miraculous Mandarin. However, before we dive into these excerpts, I think it’s important to understand some notable distinctions about the piece:

- The most performed iteration is what is commonly called the Suite, which is somewhat a misleading title. In 1925, Bartók wrote a letter to his publisher, Universal Edition, making clear his preference that the piece not be considered a ballet, but more of pantomime, since there were only two actual dances that occur in it. The Suite, therefore, is simply an extraction of the full work that has a concert ending just after rehearsal 74, and the full story is not told—it ends with the “chase scene.” Although there are some significant trombone passages that happen in the complete version, for the purposes of this article we will concentrate only on the included excerpts that happen within the Suite.

- In 2000, a new version of the complete score (which includes the Suite) was released. It is important to note here because there are indeed changes that affect some of the excerpts that we will be discussing in this article. (For more information about this new version, please visit www.bartokrecords.com.

- I do need to mention that this new version, by Bela Bartók’s son,

Peter Bartók, seems to have attracted some controversy, as some of larger ensembles who have access to a permanent loan version continue to use this 1955 version, despite having access to the new version. The reasons for this are beyond the scope of this article, but you will most likely see the new version—as all rentals are to be the new version. - With any orchestral work, it is imperative to study a score to see how your part fits. In this particular case, it’s especially important because of the trombone’s role in the piece. One would be wise to listen to several recordings before that first rehearsal!

By Rehearsal 16 to 6 bars after 17 (please refer to the score), we have already met the three thugs, who have forced a beautiful girl to attract men into their den in order to rob them. Just before Rehearsal 16, we hear music from the clarinets illustrating the girl’s seductive dance. Then, at Rehearsal 16, this Piú mosso section is led by the 1st and 3rd trombone, which portray the three thugs scurrying to hide. It’s important to know that this material, muted and with accompanied col legno strings, should be played as if portraying a family of mice looking for that elusive hiding spot. In the score, you will see that the trombones are marked at mp, with the rest of the orchestra as p. Indeed, Bartók indicated the need to be more present in the texture, and in finding the right balance of percussive articulation and depth of notes in order to create discernible pitch center takes some experimentation and collaboration with the other trombonist. I have also found that because it is muted, one may need to play stronger than the typical un-muted mp in order to achieve what Bartók has indicated. On occasion, I have seen conductors ask for more of a difference in dynamics between trombones and strings, so this section may “feel” much stronger than one might expect, but with the desired result in the hall.

At Rehearsal 17, the unsavory and perverse old man arrives in the den, and he performs lewd comic gestures in order to make light of the situation. The trombones reflect this with suggestive and provocative glissandi. These glisses need to be very present. Be sure to take care to use the kind of gliss that retains full sound throughout.

The second trombonist joins the action at this point, but it is indeed not muted, according to both 1955 and 2000 editions. Try to balance with the tuba here, and not the noisy 1st and 3rd trombones, as the goal is to provide a provocative backdrop texture for the 1st and 3rd trombone.

At 2 bars before Rehearsal 34 (Example 2) the beautiful girl successfully decoys the third man, but this time, the “catch” is no ordinary man. The thugs and the girl are horrified at the “weird figure” in the street, portrayed by the muted tritones in the trombones. The music intensifies

in the orchestra, as the trombones begin to cut through the orchestra’s texture by representing the Mandarin’s deliberate steps up the stairs. My recommendation is to play this section quasi marcato legato—ample amount of weight on the roof top accents, but with very deliberate connections to the eighths notes, almost in a march like fashion. Also, experiment with the decay on these slurred eighth notes, somewhat pulsing the air, but take care to assure the back ends of the notes still connectto the following notes. Try contrasting the accented quarter notes with sustained weight. I find myself using legato tongue throughout this passage to help with this “quasi marcato legato.” Again, this is muted by all of the trombones, so make sure to make the appropriate adjustments to reflect the proper dynamic balance.

The Mandarin enters and remains still in the doorway, and the terrified girl flees to the other side of the room. The music that depicts this entrance is truly paralyzing, and the trombones are again critical in portraying the scene, with these downward ff glisses of a minor third. I find it to be one of the most spine-chilling moments in all of the symphonic repertoire!

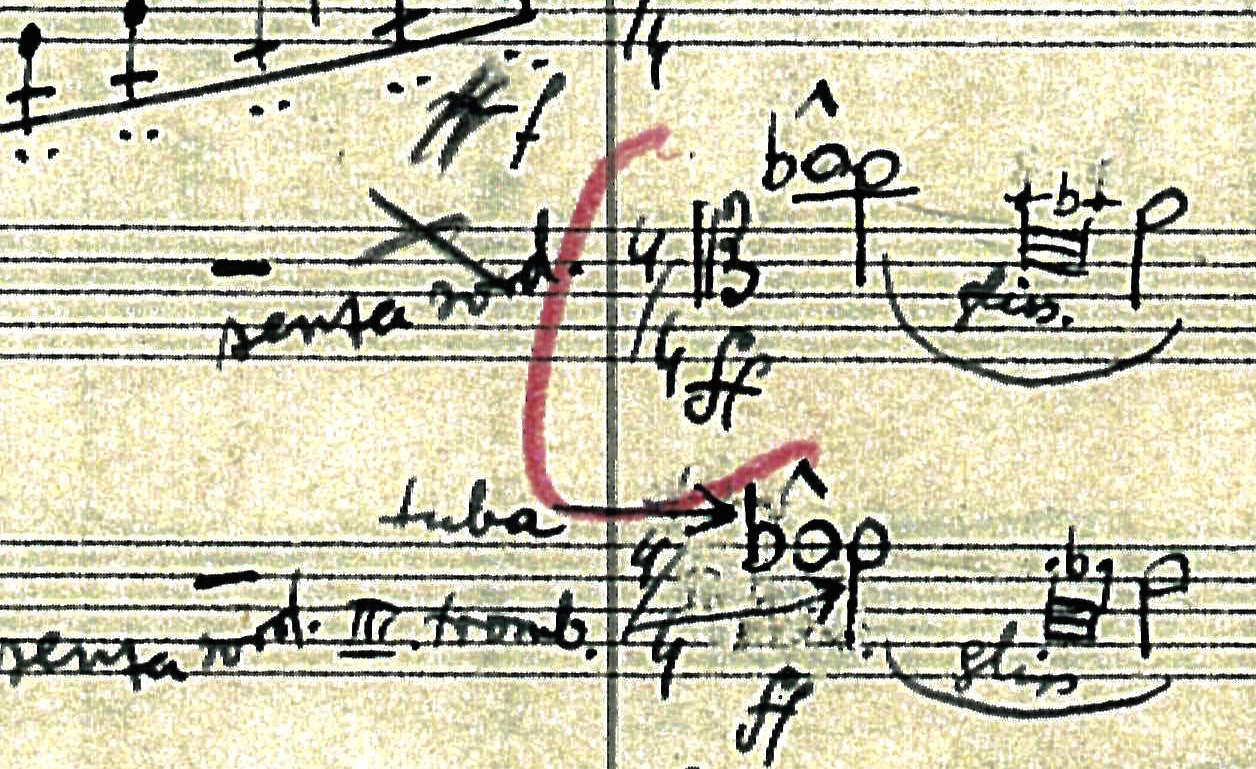

There is one discrepancy between the 1955 edition and the 2000 edition. In the 1955 edition, at rehearsal 36, the A flat to F gliss is performed both by the second trombonist and tubist. In the 2000 edition; however, the bass trombone and the tuba parts are switched, and now the bass trombone has the downward gliss and the tuba holds the A flat whole note. This is a very different timbral feel than the way it has been done for the last 60 plus years, and has caused some considerable head scratching. In hopes of gaining some insight and clarity I contacted the Bartók Society for verification/photo of the manuscript, and received the following response from Peter Hennings of the Bartók estate, who confirmed that, indeed, the new 2000 version is what the composer intended. Here is an excerpt from his e-mail to me:

“So I looked at all of our printed copies of the Mandarin score, some quite old. The original Boosey & Hawkes Rental Library score had each of the trombone/tuba parts on its own staff, and it was plain to see that trombones two and three played the gliss, while the bass tuba held the A-flat. Then came a later score in which I and II shared a staff, as did III and BassTuba. The glissando part was given down stems, which would seem to indicate that it was the Tuba part. So I sought out one of our manuscript copies, in which Bartók clarifies the confusion. He too had written all four parts on two staves, and must have realized the confusion, so he draws a line indicating that the whole note A-Flat is to be played by the tuba, and the gliss by Trb III. I enclose a photo of that section so you can see for yourself. I hope this solves the mystery.” (see manuscript example below) —Peter Hennings, Bartók Records and Publications.

Courtesy of Peter Bartók/Bartók Estate

Cropped image of above, Courtesy of Peter Bartók, Bartók Estate

Regarding the glissandi, consider starting the deliberate downward motion just after the 2 beat in order to make a more dramatic effect. Be sure to hang on to every fiber of this gliss, then retain a steady f natural in 6th position, as it creates the ominous minor 3rd interval with the A flat.

Of all the important excerpts in the Mandarin, I have found that the muted duet excerpt four bars before Rehearsal 60 to 6 bars after Rehearsal 60 tends to land on audition lists most frequently.

This excerpt appears predominately in a section round of a final audition, and is usually played alongside the other tenor trombonist. For example, I was asked to play this excerpt both in the Saint Louis audition in 2000 and the Boston audition in 2010. What is nice about this excerpt is that it allows the committee to hear how the candidate can match the other trombonist in the continuity of time, sound concept, and how they can play off of each other’s entrances, not to mention consistency in articulation.

At this point in the story, the Mandarin has looked upon the girl with an “incipient passion that is hardly perceptible,” and the music that happens at Rehearsal 59 reflects the girl finally embracing him, albeit a forced embrace, and then his “trembling with feverish excitement.” The girl then shudders with fear, and then tries to escape. In other words, we cannot be courteous with our approach in style. Careful study of this excerpt is critical. First, the second trombonist should be aware that the first two bars of the Più Allegro (half note = 104) is at an unrelated tempo from the previous music that started at Rehearsal 59 (quarter note = 144). Plus, these two bars hasten slightly to arrive at the Più Vivo (half note = 114). It’s not often that the second trombonist is allowed (or even encouraged!) to “drive the bus” in the orchestral literature, but in this case, it’s imperative to have the courage to play with authority and leadership. When I was preparing this excerpt for auditions, I played along with many of my favorite recordings in order to make sense of the tempo changes, and of course, was lucky enough to have a wonderful teacher, Joseph Alessi, to play it with in lessons.

Experiment with the length of the eighth notes—you may find that lengthening these notes, rather than trying to play them short and percussive, may yield a product that projects appropriately. The rate of accelerando that happens at the end of the excerpt requires a steady ascent to half-note = 132, so one way to practice it with a section mate could be to verbalize the articulations on the syllable “tah,” while positioning the slide.

The chase scene ensues, and we finally arrive at our last big excerpt of the Suite, Rehearsal 71, which is a wonderful “tour de force” excerpt for the low brass. In the story, the Mandarin has fallen down, but then “rises again like lightning and continues the chase

more passionately than before.” As such, the downward glissandi resulting in the minor-third intervals, in particular, need to be played with merciless abandon. The composer gives us instructions on how to treat the gliss—he uses a rooftop accent on the back-end of the gliss, which creates a raucous effect. Make sure that the glissandi (downward glissandi in 2nd and 3rd trombone, and upward muted glissandi in the first trombone) end with this roof-top accent. I suggest trying to use a “breathy pulse” to achieve the desired result. Because it’s only f at Rehearsal 71, playing a little less here will create a stronger ff effect at Rehearsal 73.

Compositionally speaking, it is fascinating to see how Bartók treats the trombone section. For example, look at the material at 6 bars after Rehearsal 72. Again, the second trombonist wears the “leadership hat,” while 1st trombonist takes a detour with some muted glissandi, then joins the section material two bars before Rehearsal 74. Bartók must have really wanted this muted glissandi, as he gives time to insert and remove the mute. For the 1st trombonist, I would recommend placing the mute in the lap before Rehearsal 68.

At rehearsal 74, the Mandarin has finally caught the girl, and then a struggle ensues. I suggest balancing these whole notes with the trumpets in order for the shrilling upper woodwinds to take precedence, then finish the piece with authority.

As you can see, there is a lot to digest! Hopefully, I have given the reader some thought on how one may begin to approach the music from The Miraculous Mandarin.

I want to thank the following for their added insight and inspiration: Douglas Yeo, former bass trombonist of the BSO; Marty Burlingame, former librarian of the BSO; Wilson Ochoa, current librarian of the BSO; and my wonderful section mates, Toby Oft and James Markey.